How to (Not) Write a Computational Physics Library

Published February 23, 2022

Before starting let’s get the disclaimer out of the way: this is not a tutorial. I am not an expert by any stretch of the imagination; to wit, my only experience with “real” C code has been working through Daniel Holden’s Build Your Own Lisp in the summer of 2020. This is only an attempt to document (heh) my progress as I write code for my computational physics elective.

Oh, and did I mention? I am going to try writing everything. From scratch. In C. And I’m writing this post to convince myself that it is not a bad idea.

Writing code for a computational physics class is weird. You are supposed to

import numpy as np right at the beginning to “make your life easier”,

but then you are supposed to forget that extremely optimized versions of

algorithms that you will naively implement over the next few weeks were

imported into your program by the very first line of code you wrote. If you don’t

want to import numpy, you could, of course, do something like class

Array(list), but then, in addition to the housekeeping, you have to bear with

extremely slow linear algebra operations in everything you write. Course

instructors don’t want you to use “any” libraries, but in practice this rule

gets extremely fuzzy: What *is* a library? Does the standard library count?

Is it okay to use objects from a library but not its algorithms? Where do you

draw the line?

The other option, if you don’t want to use “any” libraries and still have your code be relatively quick, is to use a compiled language like C++ or Rust (or Julia, if you don’t mind being a dirty cheater1).

But writing good object oriented code with C++ is hard. Getting used to Rust’s memory safety system is hard. Writing C code, on the other hand, is… also hard.

But it is also simple. C++ is very complicated.

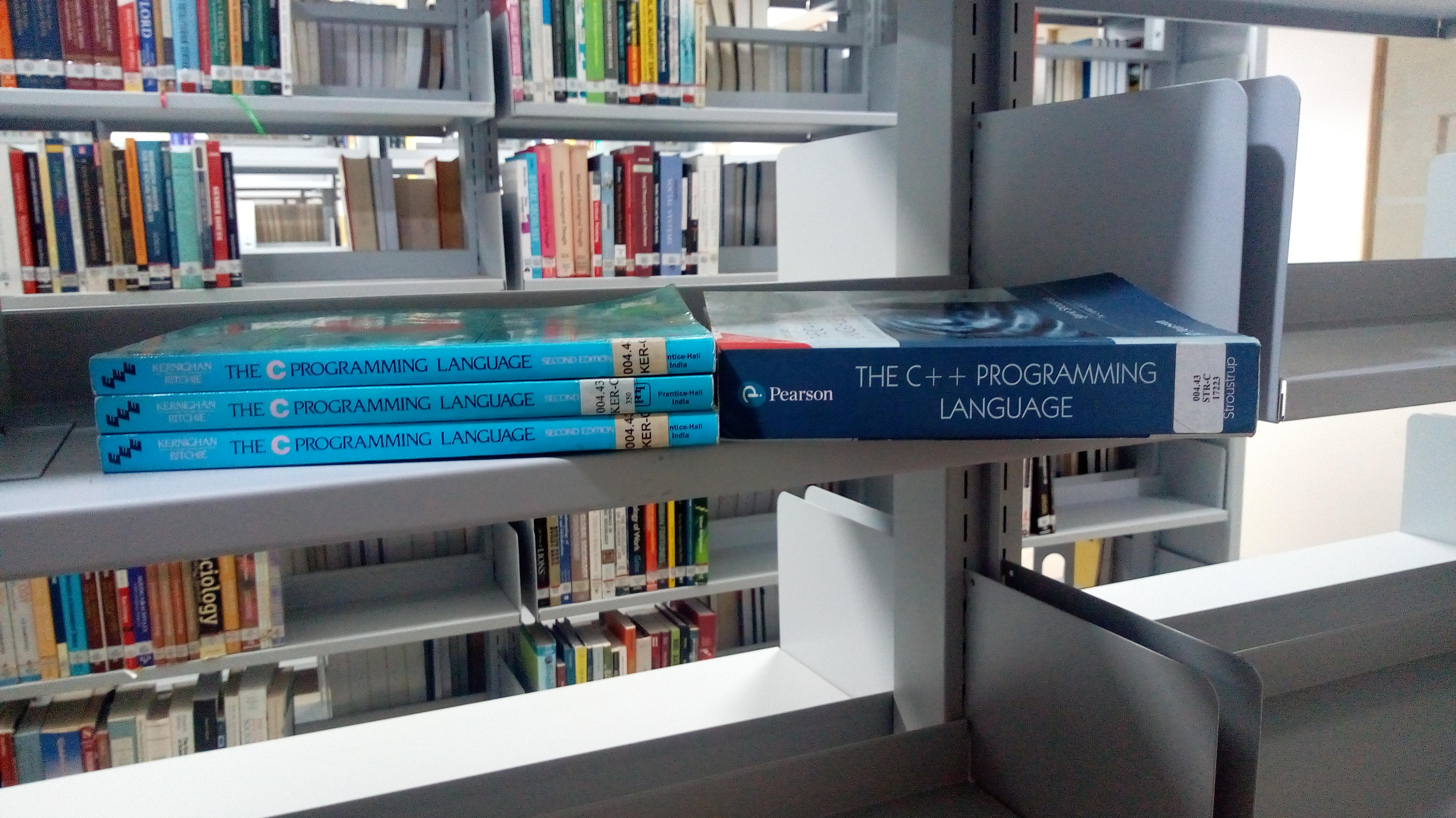

Just look at Kernighan and Ritchie’s The C Programming Language side-by-side with its C++ counterpart (Stroustrup’s The C++ Programming Language):

K&R fits a surprisingly accessible and complete introduction to C, several working examples, common idioms, and a reference for the core language and standard library, in a measly 250 pages. But this “simplicity” also speaks to a lack of features, most notably garbage collection, operator overloading, and OOP patterns like inheritance, that most people take for granted when writing code in a higher level language.

There is also the whole thing about the inescapable legacy of C in all of modern programming, which I will not recount here. I am also going to skip the metaphysics and philosophy that a more experienced C programmer would have spent several paragraphs on, but here is a quote from Why learn C?:

To want to master C is to care about what is powerful, clever, and free. To become a programmer with all the vast powers of technology at his or her fingertips and the responsibility to do something to benefit the world.

Having written a few numerical linear algebra algorithms, I have to admit, I have started to understand why people say things like this. C forces you to care deeply about your code, especially when it comes to memory. I have found myself trying to minimize heap allocations as much as possible, something I would not have given a second thought to if I were using Julia (even though the documentation suggests that I should).

In the end, there is no perfect language2. And for an application as broad as numerical analysis, there can be no perfect tool for the job3.

There is no single reason why I have decided to stick4 with C.

As far as I can tell, there is no “killer feature”. But putting together the

learning experience C provides, the challenge of working with a very simple

language, its privileged status among programmers, and (perhaps most

importantly) the bragging rights that come with writing C, spending

some extra time and effort fighting code, and beating it into shape with gdb

and valgrind seems worthwhile.